Jukeboy

Jukeboy

I launched Paperback Jukebox in 1991, and continued publishing the music and arts newspaper until it heaved its last gasp in August, 1995. More precisely, that August I “sold” the paper for $2,000—essentially the balance of outstanding ad receivables—to Rod Miller, an old friend who had also served as a features editor for significant stretches of the paper’s four-year history. As part of the terms of sale, Rod would change the name of the publication, update its physical format from tabloid to quarterfold, and tell anyone who asked that I was no longer involved with the enterprise. Thus, Blotter was born. Two issues later, Blotter succumbed from the pressures of publishing a high-maintenance zine available on newsstands for the price of FREE, thus requiring a constant flow of advertising dollars.

The last sentence of the paragraph immediately above hints at the reason for the firesale—merely adjust the timespan and substitute Paperback Jukebox in place of Blotter. After four years of publishing, I was physically and emotionally exhausted. My personal finances were in ruins. I sensed that the woman who had given birth to our daughter a year earlier was about to call our relationship quits (which ultimately proved true). As a new father, all I wanted was to successfully raise my child. Continuing to publish a local media journal that demanded nearly round-the-clock supervision got in the way of that goal. I needed out.

Serving as Paperback Jukebox’s publisher and editor-in-chief was, far and away, the highest-stature role of my working life, before and since. Before launching the paper, I wrapped my personal identity around whatever drumming prowess I managed to muster while playing in bands ranging from blues, to soul, to hard rock, to psychedelic punk, to hardcore punk, and to funk. A couple of years after launching the paper, I talked my way into drumming for an all-girl power pop band, Burning Bush. The founding members insisted I pledge to join as an “honorary girl” before allowing me to participate. None of bands I played in ever came close to landing a record deal. One of the hardcore punk bands, however, did manage to conjure up an ardent fanbase during its short existence, and the “all-girl” band’s “honorary girl” successfully pressured a local promoter into allowing our band to open for Bootsy Collins when he played Portland in 1994. Shortly after that gig, that band disintegrated, much like many of the others, victim to the same sorts of petty squabbles that scuttled so many bands with which I had squandered so much fruitless energy.

An unlikely and circuitous path steered me to my eventual role of local entertainment media impresario. After my biological father abandoned the family, my mother remarried; my new stepfather quickly joined the Army after he realized that the woman he just married came with four loud and hungry children. Soon afterwards, the military took the family away from our beloved Santa Cruz, and plopped us down in the teensy town of Copperas Cove in central Texas, just outside an Army post called Fort Hood. Almost immediately afterward, the Army shipped stepdad off to the American war in Vietnam. Shortly after stepdad returned from the war, the Army marched us to Martinez, a little town outside Augusta, Georgia, near Fort Gordon. After a year and a half there, the Army shipped the family to West Germany. I didn’t go with them, opting instead to move in with my biodad’s family, mainly because they lived in Los Gatos, just over the hill from my beloved hometown.

Almost immediately after moving in, biodad accepted a job just outside Washington D.C. Although I had no affinity for Los Gatos, relocating, once again, to a town so far away from my hometown was the last thing I wanted. The following year, I graduated high school a year early, at 16, and flew to West Germany to rejoin my other family. That fall, in 1976, I landed my first payroll job—as a retail sales clerk at the audio counter of the local Army & Air Force Exchange Service (AAFES) on Robinson Barracks, a U.S. Army post just outside Stuttgart. An even bigger perk that came along with my status as an overseas military service “brat” was access to the recreation facilities available to service members and their dependents. These rec centers had music rooms, where musicians could check out instruments to play on site. Although I once had a drum kit for a couple of years in my very early teens, I foolishly failed to take it with me when I moved in with biodad’s family, shortly after I turned 15. I managed to continue practicing drums by taking lessons, and by playing in band class at school. It was at military recreation facilities, however, where I really started to hone my craft, mainly because I always encountered other musicians, usually active-duty African-American soldiers, who were eager to launch into their next jam session.

In late 1977, stepdad quit the Army, and our family returned to the United States. Shortly afterward, my kid brother, Paul, was struck by a motor vehicle and killed. Overwhelmed by grief, I made the rash decision to join the Air Force. Within hours after my arrival at Lackland Air Force Base for basic military training, before I had completed my first 24-hours of active-duty military service, I realized that I had made an unwise choice. Immediately after completing basic training, I received orders to report for duty at Minot Air Force Base, outside Minot, North Dakota. In the late ’70s, the U.S. cold war with the U.S.S.R. threatened to heat up at a moment’s notice. Minot was a Strategic Air Command (SAC) base, meaning that it would be among the most prominent targets of a Soviet nuclear weapons attack if the cold war turned hot. Therefore base leadership became particularly displeased after poor eyesight caused me to mistakenly enter a highly secure area one cold and sleety night as I tended to my nightly tasks on the flight line, triggering a base-wide alert. Shortly after that, I received an honorable discharge and was ushered out of military service.

My short stint in the military had helped me put together enough cash to buy a nice drum kit. Upon returning to my beloved hometown, Santa Cruz, I connected with a childhood buddy, who played guitar, and one of his buddies, another guitarist. The three of us drunkenly assembled a run-of-the-mill garage band. Shortly afterward, the childhood buddy and his pal began squabbling over a woman whose affections they each sought, and the shoddy little soap opera provided me with a ready-made excuse to quit the band and seek out more interesting projects. My music interests were evolving anyway, and I increasingly found it hard to feel even the slightest interest in drumming for mediocre and directionless garage rock bands. The song writing was predictable. The rhythms felt plodding, rudimentary and offered no challenge. The cultural milieu tired and boring. I had started to gravitate towards jazz (John Coltrane, Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, Miles Davis, Art Blakey, Max Roach, Elvin Jones, Billy Cobham, etc.) and jazz-rock fusion (Jean Luc Ponty, Soft Machine, Return to Forever, Weather Report, and others). Not only was the music more interesting, the rhythms were orders of magnitude more challenging and exciting. In short order I began jamming with higher-caliber musicians around Santa Cruz, but actual bands seemed to never quite come together.

Ever since my stepdad had reenlisted into military service (having served two previous enlistments before marrying my mother), resulting in the Army moving our family to other parts of the country, and eventually other parts of the globe, I had longed to return to my hometown. I was only 12 years old when we left our neighborhood on Pearl Street, just blocks away from the mouth of the San Lorenzo river, and the beach and boardwalk. By the time I began to settle back into my hometown at age 19, I had already traveled all over the United States, and had lived in several of those states (Texas, Georgia, Maryland and North Dakota). I had also lived overseas (West Germany), and had traveled through Austria, Italy and France. I had served in, and was honorably discharged from, the United States Air Force. I loved Santa Cruz, but now it felt a bit provincial and slow-paced. My musicianship had improved considerably, as had the caliber of musicians I jammed with. But forming an actual band remained elusive. Acoustic drums, the cymbals that accompanied my drum kit, and my beloved conga drums were the only instruments I played. That, and the fact that I couldn’t write a song to save my life, meant I was reliant on other musicians to have any meaningful chance at a career as a musician.

In early 1980 I got it into my head that I should return to Europe, specifically to West Germany, in what I would later come to regard as a kind of self-imposed vision quest. In June of that year, I packed up my drum kit and conga drums, and put them onto a cargo ship in the Port of Oakland bound for the Port of Bremen. In the days that followed, I quit my job as assistant to the night auditor at Dream Inn, a beachfront resort hotel north of the Santa Cruz Wharf, and with just $300 in my pocket, boarded an airliner bound for Frankfurt am Main, the recently erupted Mt. St. Helens still smoldering as we flew over it. After landing in Frankfurt and collecting my bags, I immediately began hitchhiking south towards Pattonville, the U.S. Army housing complex just outside Ludwigsburg, where I had lived a few years earlier. By the time I finally reached my destination, I had been traveling for nearly 24 hours and was exhausted. Although only mid-afternoon, I pitched my little tent in a tiny wooded area just outside Pattonville’s northern entrance, crawled inside it and immediately fell into a deep sleep. Waking up at around noon the following day, I reflected on the predicament I had just put myself in by relocating to a foreign country on a tourist visa and without enough cash to turn around an go back if I had a change of heart. Then I began crying.

Those momentary sobs were brief; there was no use crying now, only to figure out what to do next. Having already spent a little over 10% of the $300 in cash I brought with me, I knew I’d quickly run out of money. I needed a job, so I hopped onto a bus bound for Robinson Barracks, another U.S. Army facility about 20 minutes away in hopes that my old boss at the Post Exchange (PX), Frau Beckmann, would remember me well enough to rehire me, but not enough to remember that she had fired me when I worked for her three years earlier. Her memory apparently hazy enough to not refuse to put me back to work, but sharp enough to not place me back in my old position at the Exchange’s audio counter, she instead put me to work in the store’s warehouse.

At $4 per hour, my pay was too low to afford to rent a room, even in 1980 dollars, so I alternated between sleeping underneath stairwells, in baseball dugouts, or in the open fields on the military compound. Within hours of my arrival, I began recruiting bandmates for my dream jazz-fusion band, which (in my imagination) would include horn players, an electric bassist, a guitarist, a player of many keyboards, and a master percussionist. My recruitment methods included telling anyone who would listen about my project, and by running a classified add in a local circular. The deficiencies of this approach did not take long to become apparent; after several weeks of non-stop effort, I had failed to recruit even one bandmate.

About this time, my “old buddy,” mentioned at the top of this blog post, stepped in. Far from an “old buddy” at this point (we had yet to even meet), Rod didn’t so much “step in” as “step in the way” while I gazed longingly at a lovely young woman, attempting to conjure up a witty one-liner that I could use to introduce myself to her, only for my fantasy to shatter as this pretentious-looking dude with long blond hair stepped into the frame to kiss her. Ugh! Moments later, a young Army enlistee shouted over to me, saying “hey Dave, you should talk to Rod about playing in your band. Rod plays keyboards,” gesturing towards the pretentious-looking blond dude. I dutifully introduced myself to the blond dude, telling him I played drums and was putting together a band. With a studied nonchalance bordering on arrogance, Rod replied that he was starting college in Munich in a few weeks, and would be auditioning drummers there.

This inauspicious start notwithstanding, Rod and I quickly became best buds. He had a cute sister, Betsi, who had an even cuter friend, Soheila, who quickly became the crush of my 20 year-old life. After I got word that my drum kit had arrived at the Port of Bremen, Rod agreed to hitchhike up there with me to help with next steps in getting my precious cargo to its new home. The plan was to get up there and transfer my drums onto a train bound for Stuttgart, an adventure that would need its own blog post to adequately account for. Shortly after my drums arrived in Stuttgart, I accompanied Rod down to a University of Maryland-affiliated campus outside Munich, and moved right into the student dorm apartment the actual student shared with two other legit students; all three of whom tolerated me taking up residence in a corner of the dining room.

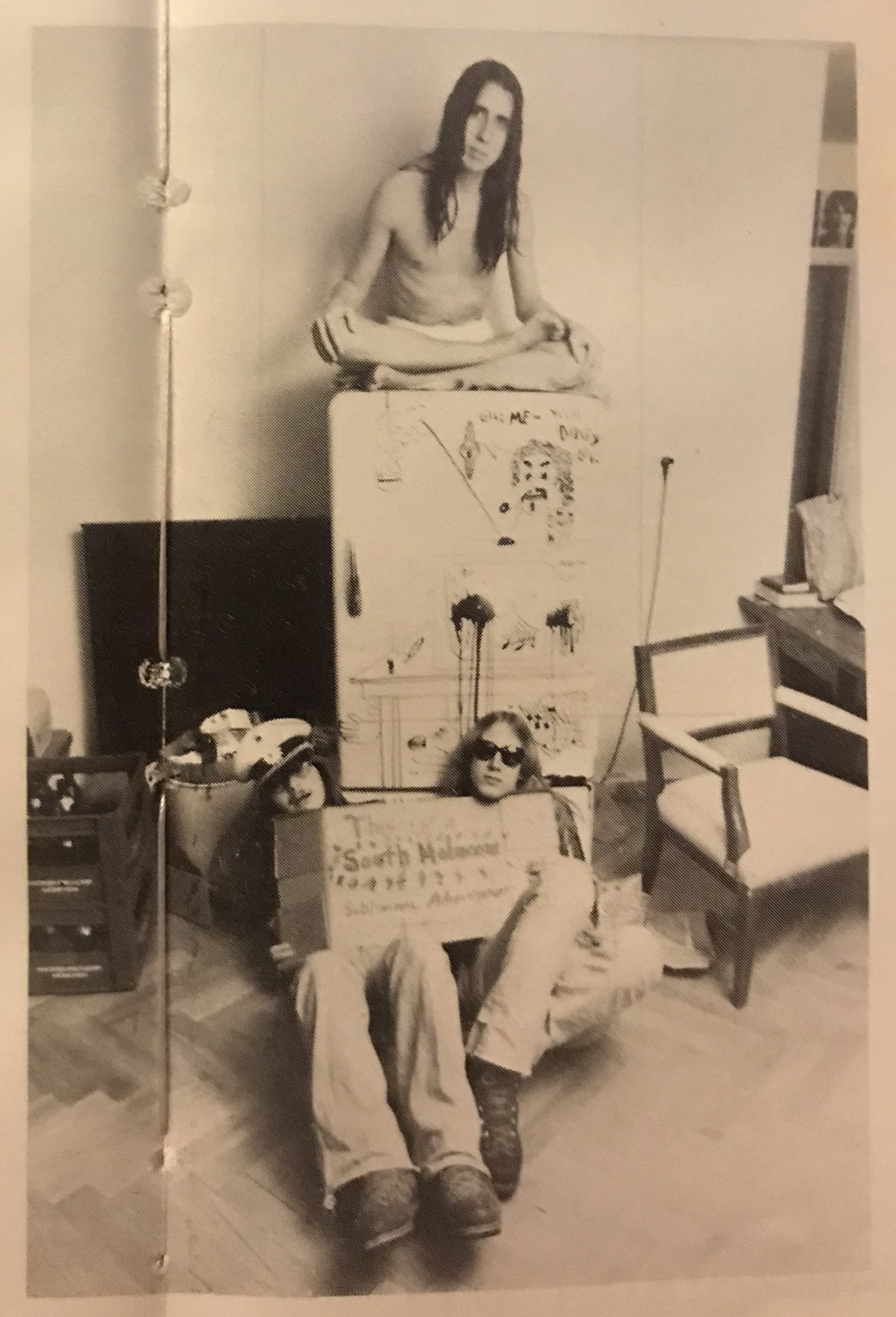

Clockwise from top:

David “Molucca” Myers (drums), Rod Miller (keyboards), George Burns (bass).

Not pictured, Russ Kewl (guitar).

Munich, West Germany (circa 1980).

Once on campus, we quickly commandeered an excellent practice space and put together a psychedelic-punk band we called South Molucca. The actual South Moluccans our band name referred to were a group of suicide commandos who had hijacked a train in 1977. None of us could recall exactly what the Moluccans’ grievances were, but the badassery they demonstrated by hijacking a train carried an exotic wild west bravado that more well-known revolutionary gangs of that era (e.g., Red Army Faction, Red Brigades, Symbionese Liberation Army) lacked. None of us were songwriters, so we cobbled together setlists comprised of an eclectic assortment of cover tunes we did our best to put our own original spin on. Ultimately, the band was a short-lived project; we played only a handful of on-campus shows in Munich, and one show in Stuttgart before misfortune caught up with the band in the from of motor vehicle accident. Traveling back to Munich after our Stuttgart gig, the VW van we had borrowed from Rod’s mother was struck by a disabled vehicle under tow that had broken free of its tether. Our vehicle began fishtailing, but our driver (and bassist) George Burns managed to keep the van from flipping, saving all of our lives, apart from that of our borrowed vehicle’s engine, which blew up. Rod’s mom and stepdad were so furious that they exacted punishment, the details of which I have long forgotten, but whatever it was, it was enough to break up the band. The college also banned us from our practice space, for reasons I have also forgotten.

Space in this blog post does not permit going into detail about other Munich-based hijinks, like the barroom brawl I didn’t exactly mean to provoke. Nor to adequately account for an infamous trip through Italy, driving a VW Bug with bald tires I had bought off one of the students on campus, which was actually owned by her CIA analyst father. When the CIA-dad finally tracked me down to demand I tell him where his car was, I admitted that I had abandoned the vehicle in Italy. At least I had the presence of mind to not provoke him further by dramatizing the harrowing ten minutes or so that I got that little VW bug to outrun a military police jeep stuffed with submachine gun-wielding Italian military police commandos on the streets of Bologna.

Not long after hitchhiking back to Munich after abandoning the little racecar equipped with sporty bald tires in a hotel parking lot north of Milan (the vehicle was out of gas, and I was out of cash), I made my way back to Stuttgart and took a prep-cook job at a U.S. Army officer’s club at Robinson Barracks. It was the beginning of the end of my self-imposed European vision quest. I could feel that I was running out of steam. Crappy wages and no student housing immediately available to Hausbesetzung , meant entering a second season of sleeping in baseball dugouts and open fields. If I really needed indoor shelter for a night or two, I no longer had to resort to sleeping underneath stairwells; instead I had gotten clever enough to sneak up to the top floor of one of the residential buildings, where I could usually find an unused “maid’s room” to squat in for the night. In fact, it was while sleeping in one of those attic spaces that I found myself returning to consciousness lying face-down on the floor with a broken nose, gashed lips, smashed-in teeth and soaking in a pool of blood. I had woken up in the middle of the night, wandered to a bathroom down the hall, then passed out. Exhaustion from a year and a half of high-energy hard living had finally caught up with me.

Profound fatigue was just part of the problem. My closest friends were also all leaving the country. My best bud, Alireza, and his beautiful sis, Soheila (the girl I had a crush on, and who broke my heart), moved to Istanbul. Rod, my best bud and former South Molucca bandmate flew back to the U.S. to begin classes at the University of Idaho. I would have happily shacked up with his cute sis, Betsi, but their mom wouldn’t stand for it. Short on cash, and my face still a mess from my unfortunate collapse in the bathroom, I wandered down to the local Ausländerbehörde (Foreigners’ Office) in Stuttgart to try and get myself deported back to the States. An official there asked me how long I had lived in the country illegally. “Over a year,” I replied. He said something along the lines of “well, it looks like you’ve got this figured out, so just keep doing what you’re doing.” Since the West German authorities were too frugal to fly me back home, I’d need to keep working for another month or so in order to save up for the next flight out of there. Another way I tried to raise cash was by putting my Pearl drum kit, Zildjian cymbals, my super-sweet Gon Bops conga set up for sale. Much like the cowboy who was “lookin’ for luv in all the wrong places,” I was apparently looking for drum buyers in too few spaces by advertising in the same circular that got me exactly no results while trying to recruit bandmates a year earlier. I took a gamble by entrusting my music instruments with the manager and the supervisor of the Officer’s Club where I worked after they offered to sell them for me and then send me the cash, even though they were two of the most untrustworthy Army sergeants I’d ever met.

Predictably, my foolish gamble did not go my way. Once back in the States, my former bosses, the wretched little duo who managed the Officer’s Cub, claimed I had never worked at their club, and that they had no idea who I was. The California employment office quickly established that I had indeed worked there, and made good on my unemployment insurance claim. But once again, I found myself without a drum kit, bereft of my prized Gon Bops congas, broke and jobless. Another wrinkle had emerged in my absence: my mom and stepdad had sold the family home on Pearl Street in Santa Cruz, and moved to Red Bluff, a dusty little backwater bisected by the northern leg of the Sacramento River. The only family remaining in the Santa Cruz area was biodad’s household, situated in the hills above Scotts Valley, a sleepy little Santa Cruz suburb. I certainly didn’t want to barge in upon the Scotts Valley hillbillies, but I most definitely didn’t want to hang out in Red Bluff. What to do? Within hours of opting to take temporary shelter with the biodad household, it became obvious that I had made an unwise choice. Biodad’s wife complained loudly and bitterly about my presence under her roof to anyone willing to stay on the phone with her long enough for her to express her travails, grievances and sorrows. After a month or so, biodad himself whipped out the “tough-love” card and railroaded me out of the house.

In Red Bluff, mom and stepdad welcomed me with open arms, and nursed me back to some semblance of functional post-exhaustion. While in Europe, my entire wardrobe (which wasn’t much) had deteriorated to not much more than rags. Mom bought me a new outfit so I could look presentable enough to interview for a job. The small-town Red Bluff economy in early 1982 was at a near standstill, but by some miracle I managed to land a library assistant job at the Tehama County Library, which nearly every unemployed person in the county also seemed to covet. At the same time I began making plans to put together another band with my old bandmate, Rod Miller, and Joel Kreager, one of our friends from the Munich campus. Scattered up and down the U.S. west coast, the three of us began deciding on a city to move to and launch the band. We had narrowed the choices down to San Francisco, Portland and Seattle. One of Rod’s college chums, bassist Kevin Budge, also wanted to join the band. Kevin had a girlfriend in Portland, so we all decided to resettle there. By early June, after only about three months’ employment with the library, I had managed to save up enough money to barely get me to Portland, and soon settled into my new room in a large house we all shared in the Overlook neighborhood, near Overlook Park.

For reasons I am unable to fully recall, the attempt at forming a band failed almost instantly. Rod took off for Europe shortly after one of his European girlfriends came to Portland to drag him back to the continent. Kevin (Rod’s bassist pal who also wanted to “join the band”) moved into his girlfriend’s Beaverton apartment, and Joel enrolled in the Ali Akbar College of Music. Soon afterward, Rod’s Portland girlfriend, a young beauty named Mary Elizabeth, called the house, looking for Rod. I had picked up the phone, and found myself awkwardly and profusely apologizing for having to break it to her that Rod had left the country. Somehow Mary discovered that I had a birthday coming up, so she baked me a cake, and brought it over while I was away from the house. A housemate took it and placed it in the oven, forgetting to tell me about until three days later. Seconds after the housemate belatedly informed me of the cake, I called Mary to apologize once again. We began dating shortly afterward.

Not long after Mary and I began dating, I auditioned to play drums in The S.L.A. (referring to, without apparent irony, the Symbionese Liberation Army). The hardcore punk trio offered me the drummer role almost instantly. They’d never had a real drummer until I came along and made it a quartet. Band leader, Derby O’Donnell, his lovely wife, Laura, and singer, Peter Nelson wrote all of the songs, each of which the band blitzkrieged through in just about one minute, give or take a few seconds. Laura was a talented bassist, but it was her beauty and charm that helped us land nearly all of our gigs, except for our show at Metropolitan Learning Center (MLC) in Northwest Portland. I landed that gig as a result of a traffic stop, which led to a court date and a $30 fine I was too broke to pay. After the judge ordered me to pay up or face jailtime, I replied “well I guess I’m going to jail because I don’t have any money.” The judge offered to let me get off with community service instead, resulting in our gig at the alternative K-12 school. The show ended after the school’s principal pulled the plug, but the kids loved us. Derby kicked me out of the band a few months later after I refused to show up for a last-minute rehearsal session because I had plans to take Mary out on a date that evening.

At this point, my hardcore punk drummer credentials were firmly established, at least within the Portland punk scene. A group of punk kids—Ken Kissir, Ian Miller and Sean McClain—had started a punk combo, and for reasons I can no longer fathom, I had agreed to allow them to make my basement their rehearsal studio. Initially I had rebuffed their attempts to drag me into the band, but their persistence finally paid off, and the four of us formed Witch Doctor. We played our first gig before we had even nailed down our name after I asked the promoter of a multi-band punk festival, already in session, why he hadn’t featured our band in the lineup. He responded with “what’s the name of your band.” I blurted out “The Rock ’n’ Roll Extremist Faction”—the first band name idea I could think of on the spot. The promoter agreed to sandwich us in for five minutes after the current band completed their set. Ken, Ian and I rushed back to my house to grab the equipment, then got onstage and played a half-hour long grunge-like dirge which ended only after the promoter literally pulled the plug.

In the months that followed, Witch Doctor served as the house band for 13th Precinct, an all-ages punk club located at 422 SW 13th Avenue, which operated from about 1982-85. The club’s booking manager relegated us to the opening act in every show we played; I don’t recall Witch Doctor ever headlining a show there. However, we did manage to open for quite a few notable punk bands of that era, like the Dicks (who gave us their “big dick stamp of approval”), GBH (who seemed too strung out, or perhaps just too sleepy, to realize that a band had even opened for them), and Seattle’s Fastbacks (who expressed genuine enthusiasm about our performance each time we opened for them).

Witch Doctor’s most infamous gig was also our last, and took place across town at a short-lived venue called Rock Palace (SE 64th Ave & SE Foster Road). Our bassist and band leader, Ken Kissir, booked the show. The promoter shoehorned us in with three non-descript hair bands. In those days, that part of Southeast Portland was often inhospitable terrain for hardcore punks, who tended to congregate downtown, or the very close-in east side. Lone punks who ventured out that far, into what was essentially “edge of town” in those days, were sometimes physically attacked. Only a couple hundred or so of our biggest fans (physically the biggest, that is) showed up for that show, every one of them congregating in the first few rows nearest the stage. The hair band fans kept to the back of the hall. On stage, each of us “witch doctors” were nearly falling-down drunk. I cannot comprehend how we got through our entire set in that condition, but we played with a ferocity that outmatched any of our previous gigs, the tamest of which were always on fire. My drum kit, teetering on its shoddy hardware, continuously fell apart around me due to the intense beating I unleashed on it, forcing me to somehow cobble it back together in mid-song with one hand, even as I kept the beat with the other. In between songs, our fans roared with approval, accompanied by their backing vocals from the hair band crowd who howled their disapproval. After our set, the four of us in the band hung out in the front of the building, chatting with our punk fans. At frequent intervals, one of the hair band audience members furtively snuck up, looked around to make sure none of her/his friends were watching, and then blurted out a few syllables of cautious admiration before disappearing back into the night. The band broke up within days of playing that gig, for reasons I can’t fully recall.

My half-year run with Witch Doctor, and all of the antics I engaged in during that span, put a severe strain on my relationship with Mary, a strain that would ultimately lead to the relationship’s demise. But troopers that we were, we managed to punish each other for another four or five years before finally calling it quits, although I shouldn’t express this in such a glib manner; I truly loved that woman. Before throwing in the towel, however, we managed to launch a vintage clothing store, naming it Chaos/Kontrol. Ahead of its time (early-mid ’80s Portland wasn’t quite “there” with hipster fashion, yet), the store barely made any money, but Mary made it an artistic and off-beat cultural success anyway, putting on underground fashion shows in derelict warehouses situated in what would later become Portland’s Pearl District. Mary’s enthusiasm for the store faltered after we were forced from our store’s first location in a small loft area above a small fashion design collective, on SW Oak St., just off of W. Burnside St., and right next door to one of Portland’s hippest record shops, Singles Going Steady. The collective’s founder, a recent transplant from San Francisco, sold it to a group of designers who were part of the collective. One of Mary’s friends, designer, choreographer and dancer Keith Goodman, who contributed his fashion designs to the collective, made a valiant but ultimately unsuccessful attempt to dissuade the new owners from kicking us out of our space.

During all this, I once again got the itch to climb back onto the stage. Already sick to death of the Portland punk scene by the mid-’80s, I was ready to try something completely different. One day in late ’85 or early ’86 my buddy Andrew Loomis dragged funk bassist and songwriter Henry Jhunne “J.R.” Brogdon over to the inner-southeast Portland house Mary and I shared with Andrew and a couple of other housemates. A drummer who had played multiple Portland power-pop and psychedelic proto-grunge bands, Andrew’s initial intent (best as I can recall) was to test out new musical terrain. Though an extraordinarily talented bassist, J.R. struggled to adjust his playing to Andrew’s garage-rock style of straight-ahead drumming, so I asked if I could sit in. Portland’s answer to Bootsy Collins and I immediately settled into a heavy funk groove. Within hours, we were putting together a band that would become Freak Control. Mike Metzner joined to play keyboards. Ian Miller, from my old band, Witch Doctor, stepped in as our first guitarist. A talented and versatile young guitarist, Ian picked up funk almost immediately, but quit the band within a few weeks to return to his hardcore punk roots. Guitarist Michael Richardson quickly filled the spot Ian vacated.

Mike Metzner also sang and played keyboards in the local Tex-Mex orchestra, Poli Chavez Y Sus Coronados, and convinced bandleader Poli Chavez to let us open for them on their Portland gigs, which always happened at the Melody Lane Ballroom. Although we were a funk band, and our sound was nothing like the Tex-Mex/Cumbia/Ranchera Poli’s audience came to see, they never failed to greet Freak Control enthusiastically. And that audience loved to dance! We opened each show with our flagship song, “Dance,” an up-tempo, hard-driving and heavy funk back-beat dance tune that showed off J.R.’s prowess on the electric bass and got people instantly on their feet every time. Another venue we played frequently was Satyricon, the so-called “CBGB of the West Coast,” where we generally opened for The Flapjacks, a local Rockabilly trio. If I recall accurately, J.R. was friendly with Flapjacks’ Louis Samora, which probably helped secure our opening spots. Even so, the entire band seemed to genuinely like our sound.

For me, the two most memorable Freak Control gigs took place at a couple of other venues: Pine Street Theater, and a small hole-in-the-wall tavern on the North/Northeast side of town (probably on NE Alberta Street, long before it was gentrified into the Alberta Arts District, the name of which escaped my memory decades ago). At the Pine Street Theater, Freak Control appeared with a number of other local bands as part of an all-day music festival. Also on the bill was another “funk” band put together by a group of Reed College students. While we setting up the stage to do our sound check, the bassist from the Reed College band began showing J.R. some of his bass playing chops. Nodding solemnly while stroking his chin, J.R. politely took in the kid’s innocent foolishness. Watching all this out of the corner of my eye, it became clear that this kid hadn’t yet grasped that wild animals roamed Portland’s city streets who could—and would—eat him alive. When J.R. climbed onto the stage to launch us into our sound check, the kid quickly got nervous. A few seconds later, after I kicked the beat into high gear and J.R. unleashed one of his more impressive Bootsy-esque riffs, the kid literally ran out of the hall. The Alberta Street gig, one of our first, was completely different. We were the only band playing there that evening; everyone in the audience was African-American, and several of these folks eyeballed me with noticeable skepticism as I set up my drum kit, possibly wondering what this freaky-deaky long-haired dude was doing with the more legit-looking musicians. On the other hand, I couldn’t wait to get started because I knew that I was just about to make believers out of everyone in that room. Our gear all set up, we launched into “Dance” without even bothering to rush through a preliminary sound check. About half a second after finishing that opener, someone in the audience loudly blurted out “Damn! That white boy be kickin’!”

After a few months, Freak Control broke up for reasons that, just like so many of my previous projects, are too forgettable to remember. My 27th birthday loomed later that year as it sank in that my dirtbag musician lifestyle was not aging well. Worse still, my relationship with Mary continued to slide further and further into the abyss. In retrospect, warning beacons that something in our relationship was not quite right were hard to miss—whether it was the fiery daggers darting from Mary’s eyes as she held the butcher knife up to my throat, or the firmness of her grip on the two-by-four she used to wallop me upside my head, or the velocity of the leaded glass bottle she threw at me as it rocketed past my nose before slamming against the wall and shattering into a zillion pieces, or the throbbing ache I felt as I came to in the wee hours of the morning from a drunken slumber to encounter Mary’s fist pummeling my face. That last episode actually pissed me off, so I called the cops. When the officers arrived, all they saw was an innocent-looking featherweight beauty, and me. They responded with a couple of insults hurled in my direction, then stomped out. “Fuck you!” I said. They replied in kind, without even glancing back as they slammed the door behind them. Mary had been staying with her friend, Holly (where she had given me the face pummeling). Shortly afterward, she moved up to Seattle to stay with her older half-sis. Not quite done with each other yet, I traveled up to Seattle at regular intervals to be with her, and we would have lots of fun. After I suffered a partial retina detachment in my right eye, Mary immediately moved back to Portland to nurse me back to health after surgeons reattached the retina. I had been sharing a small apartment on NW Upshur St. with my buddies Andrew Loomis and Jim Michels, so Mary and I found a small Victorian house to rent about a block away on NW 24th Place. Once again, our relationship took another nosedive. When I suggested that maybe we should call our relationship quits, she perked up, her face brightening as she exclaimed “really!” with a hopeful note left little to the imagination. Not long afterward, she married an investment banker, moved into mansion tucked away somewhere in the west hills, and gave birth to two lovely girls.

While unsuccessfully attempting to salvage my relationship with Mary, I began fishing around for alternatives to slogging from one band failure to another as a talented but ne’er-do-well rock-punk-funk drummer. I asked my job counselor at the state employment department if he could enroll me in a job training program, and it turned out he could! Better yet, the program would pay me a $10 per day stipend for every day I showed up for training. I had no idea how I would pay rent on a fifty dollar a week income, but figured I could worry about that later. Training took place at Portland Community College’s Southeast campus, then located way out on SE 82nd Ave. between Division and Powell, where the Fubonn Shopping Center sits now. The training encompassed basic office skills: typing, business math, business English and job interview preparation. Although I had graduated high school in 1976 one year ahead of my class, my accelerated departure did not come about due to any academic merit, but because I told the school counselor that I would “only put up with one more year of this shit,” and threatened to make an even greater nuisance of myself than I had already if we couldn’t find a way for me to grab an early diploma. My long-suffering counselor explained how I could attend summer school, then move right into my senior year, skipping the eleventh grade entirely, so I took her up on it. It turned out that I actually enjoyed myself at summer school, becoming the most popular kid in my English class. Similarly, I enjoyed the job training program too, and decided to follow it up by enrolling as a full-time student at Portland Community College’s Sylvania campus that fall.

Shortly after beginning classes at PCC’s main campus, I found myself transitioning from chronic underemployment, to working three part-time jobs while taking a full class load. My buddy Rod, who had landed a job as a record store sales clerk at Music Millennium’s westside location on the corner of NW 23rd Ave. and NW Johnson St., put in a good word on my behalf to the store’s manager, Doug Peabody. That good word landed me an interview, followed by a job offer. I reported to my other two jobs—as a reporter and paste up artist with the student newspaper, The Bridge, and as an assistant in the campus’s computer lab—between classes on campus. Oren E. Campbell served as the student paper’s publisher and editorial advisor at that time (late 1980s). As the idea of launching a Portland-based music and arts monthly newspaper began elbowing its way past my better judgement, Oren patiently and generously offered his advice and guidance.

By early spring 1991 I had set a September launch date for Paperback Jukebox. Later that spring, my small team—which included my musician and artist pal Takafumi “Tak” Ijuin (伊集院 貴文) and a handful of other friends—prepared a preliminary mock-up that we referred to as the pre-dummy issue, which we circulated among friends and potential advertisers to generate interest, and to assemble an initial group of contributors. My close friend, Deanna Marcus, and my buddy, Darren Lacey each stepped in with small cash contributions to help defray initial expenses while also offering much needed feedback, encouragement and guidance. A month or so later, I drove 173 miles north to pay a visit to The Rocket’s Seattle offices where I announced my plans to that paper’s editor, Charles R. Cross, and other staff. At that time, The Rocket was the publication most closely resembling the vision I had for Paperback Jukebox, and my foolish bravado in announcing my intention to begin publishing in Portland may have influenced their decision to begin publishing The Rocket’s Portland edition (although I’m far from certain if I am remembering these details with complete accuracy). A full-fledged eight-page dummy issue, featuring reviews, an advice column, low-brow humor, and advertising rates, followed Paperback Jukebox’s pre-dummy, allowing me to begin selling ad space in earnest. Paperback Jukebox published its first issue on schedule on schedule, on September 1, 1991.

The title of this blog post you’re reading now started off as “Paperback Jukebox.” Multiple paragraphs in, and after several weeks of writing, this post had clearly morphed into a superficial account of the first several decades of my life as I—with only partial success—tried to work out what drove me to launch that venture. Original mission unaccomplished, I renamed the post “Jukeboy”—the name of the paper’s cartoon mascot. David J. Myers (me) founded, edited and published Paperback Jukebox. Deanna Marcus and Darren Lacey provided initial seed funding for the paper’s initial launch, with Deanna serving as our original advertising manager. Denise Duncan served as our first managing editor. Takafumi Ijuin was the paper’s original illustrator and design editor. John Eckenrode served as the paper’s photo editor and design manager for the first two-plus years. Marne Lucas, Jessica Richman and William Abernathy contributed as associate editors at launch, with Marne transitioning to the paper’s Urban Jungle editor in later issues. Alongside Tak, Peter Greaver and Chris Lowenstein contributed artwork and illustrations at launch. Nikki Brussard, Jim Cser, Stephanie Eden, Les Evans, Sean Farrell, Annie Campbell, David Gottfried, Carl Hanni, Mairi Hennessy, Dave Hollingsworth, Phyllis B. Lowe, Tito Matos, Patrick Mazza, Griff McClellan, Chris Merrow, Dan Renner, Ted Thieman, Brad Tyer, Robert Verde and Mike Zisk contributed writing to the inaugural issue, with many continuing to contribute for significant stretches of the paper’s lifespan. Along with John Eckenrode, Dave Clothier, Danny Jiles, Paul Kearney and Dave McCarthy contributed photography.

Over its four-year lifespan, Paperback Jukebox received widespread acclaim, won awards, and helped lay the foundation for a much fresher and more vibrant Portland music scene. In addition to those listed above, many other contributors would come aboard and contribute to the paper’s success. But since I have committed to contributing one new post on this blog every month, and since the time to publish the latest new post has arrived, I will have to tell the paper’s actual story in another blog post, or if I ever launch a full-fledged Paperback Jukebox website, perhaps I can tell the story there. But since more than three decades have elapsed after the paper published its final issue, you may not want to hold your breath.